This week I’ve been staring at a collection of just over 29,000 PDFs. Image-only copies of thousands of documents created with “..the software that came with the scanner.”

My task? Figuring out the right tools and workflow to get these PDFs through an OCR process so we can unlock the content and make them more accessible. A number of these documents will end up in our MARS system, so exposing the text to the PDFBox indexing code that ships with DSpace is critical (as an aside, I’ve heard that Xpdf is a really nice replacement for PDFBox but I haven’t had time to tip it into our DSpace install yet).

I don’t have a precise OCR accuracy threshold in mind but assume if we can hit the mid-90% range we’ll find that retrieval doesn’t suffer.

I have seen a 2001 study by a group from Harvard University Library that found that 96.6% of searches will succeed on uncorrected OCR’d text. Also worth a look, Rose Holley’s recent article in D-Lib Magazine (“How Good Can It Get?“). She offers a number of interesting ideas on improving OCR accuracy in a large-scale digitization project. For some reason, it seems that most of the literature on OCR accuracy and retrieval focuses on scientific literature–where it appears to make very little difference. [ article behind pay wall ] [ freely viewable version ]

An ideal workflow would look something like this: fill a directory with image-only PDFs and point some sort of OCR process toward it. The final product would be yet another directory that contains “image-over-text” versions of the original PDFs (wherein the OCR’d text resides ‘inside’ the PDF as an extra ‘layer’ of content).

I’m trying out Mac-based solutions first (knowing that if it ends up being a Windows-based workflow we’ll likely use OmniPage (a product we already use with our ATIZ bookscanner)).

I’ve processed just over 500 of the PDFs and can’t yet say that I’ve found the ideal workflow but I thought it might be useful to report my preliminary findings…

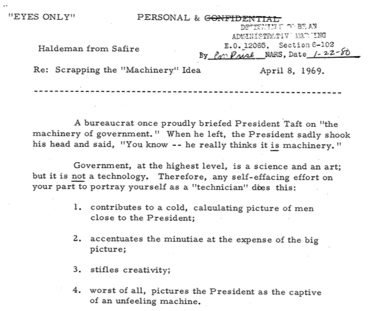

First, here’s an excerpt of one of the PDF files, followed by the OCR work done by a variety of software packages:

Fastest Solution

Adobe Acrobat Pro 9.1.3. Blazingly fast. Not so evident in this sample, but across a number of PDFs it’s clear that it is only slightly more accurate than the proverbial room full of typing monkeys.

"EYES ONLY"

PERSONAL & GG:NFiDEJ:'{fl'IAtr' tT".\-, B:'?...A:"')l D\F'~IT~.~~T.~~r

E. O. 1206i5, S,ectio!16-102 By tN1~fMAt__NlAiRIS,Date I~2-Z-fD

A pril 8, 1969.

·!

Haldeman from Safire Re: Scrapping the "Machinery" Idea

A bureaucrat once proudly briefed President 'Taft on

"the machinery of government. " When he left, the

President sadly shook his he.ad and said, "You know -

- he really thinks it is machinery. "

Government, at the highest level, is a science and an

art; but it is not a technology. Therefore, any

self-effacing effort on your part to portray yourself

as a "technician" dres this:

1. contributes to a cold, caluulating picture of men

close to the President;

2. accentuates the minutiae at the expense of the big

picture;

3. stifles creativity;

4. worst of all, pictures the President as the captive

of an unfeeling machine.

Easiest Solution

DevonThinkPro Office.

With a built-in OCR capability (provided by the ABBYY FineReader 8.x SDK), I select “Import->Images (with OCR) and point the program to a folder full of PDFs. Slowly but methodically, the files are imported, OCR’d and converted to PDF+Text files. Since DevonThink also provides full-text indexing (and a web-based search engine), I can quickly figure out how well the OCR is working. Downside? Very slow but I like the accuracy. How slow? Just over 72 minutes to process 36 PDF files on a fast machine; however, several of these files were 50+ pages long.

"EYES ONLY" TT ,, PERSONAL & CONFIDENTIAL D'S"rirr."T.,TT T-B!?,.o AD!ivIKiS'TR)',:TiV' BAH'IKO e ,. E.O.120S5, Section6-102 • , Haldeman from Safire Bv ^ ffW^MAKS, Date l-^ft> Re: Scrapping the "M achinery" Idea A pril 8, 1969. A bureaucrat once proudly briefed President Taft on "the machinery of government. " When he left, the President sadly shook his head and said, "You know -- he really thinks it is machinery. " Government, at the highest level, is a science and an art; but it is not a technology. Therefore, any self- effacing effort on your part to portray yourself as a "technician" does this: 1. contributes to a cold, calculating picture of men close to the President; 2. accentuates the minutiae at the expense of the big picture; 3. stifles creativity; 4. worst of all, pictures the President as the captive of an unfeeling m achine.

Exasperating but Promising Solution.

ReadIRIS 12 Corporate Mac.

This is a new product (released just last month) and, based on what I’ve been seeing, one that’s not quite ready for OS X 10.6. Due to the annoying registration procedure (you type in a key then await an email giving you the rest of the registration handshake), I can’t put the software on 10.5 box to see if it works better there.

It does handle batch processing and it’s quick but it also crashes (fails silently) during a batch process, typically after it has processed 10-15 documents. I sent a few crash dumps to IRIS support and received back just one hint: force the program to load in 32 bit mode (via a GetInfo checkbox).

Tried that but it didn’t work. The batch processing app wasn’t honoring the setting on the ReadIris.app. I later had the idea of drilling down into the ReadIris.app (like most apps on the Mac, it’s really a directory) via “Show package contents” and in fact was able to then set Batch.app to 32-bit operation. That helped but didn’t solve the problem. ReadIRIS would process 20-25 files before crashing yet again. Still waiting to hear back from tech support with a fix for this…

As you can see, there are accuracy issues as well (“space” recognition doesn’t seem to work as well as the “character” recognition):

"EYESO~LY" PEMO~AL&G9NftDEKTmt By t1O~f7~ ~S, D'ate I~~~-.~ April 8, 1969. ~ FIaldennan fronn Safire Re: Scrapping the "~achinery" Idea ------------------------------------------------------------ A bureaucrat once proudly briefed President Taft on "the nnachinery ofgovernnnent. II Vfhenheleft,thePresident sadlyshook hisheadandsaid,"Youkno\W -- hereallythinksitisnnachinery." Governr.nent, at the highest level, is a science and an art; but it is not a technology. Therefore, any self-effacing effort on your part to portray yourself as a "technician" dOes this: 1. contributestoacold,caluulatingpictureofnnen close to the President; 2. accentuates the nninutiae at the expense of the big picture; 3. stiflescreativity; 4. \Worst of all, pictures the President as the captive of an unfeeling nnachine.

Finally, because I find it a fascinating document (and because Mr. Safire has been in the news this week), I offer a cleaned-up version of the memo for your enjoyment. For those of you too young to remember, Haldeman was Chief of Staff in the Nixon White House. Mr. Safire was working in the new administration as a speechwriter.

As you can probably tell from the memo (written in the first months of the new administration), Mr. Safire’s background was in public relations. I’d like to think this is the sort of thing they still study in management / communication classes…

“EYES ONLY”

PERSONAL & CONFIDENTIAL

Haldeman from Safire

Re: Scrapping the “Machinery” Idea

April 8, 1969.

A bureaucrat once proudly briefed President Taft on “the machinery of government. When he left,the President sadly shook his head and said,”You know–he really thinks it is machinery.”

Government, at the highest level, is a science and an art; but it is not a technology. Therefore, any self-effacing effort on your part to portray yourself as a “technician” does this:

1. contributes to a cold, calculating picture of men close to the President;

2. accentuates the minutiae at the expense of the big picture;

3. stifles creativity;

4. worst of all, pictures the President as the captive of an unfeeling machine.

I have put this in extreme terms so as to jolt you into careful reconsideration of the public side of your own role. Like it or not, there is a public side to what you do. Your choice is not publicity or no publicity; it is either good or bad publicity. Cloaking your operations in secrecy, or even in the guise of being “only a technician,” means bad publicity for the Office of the President.

Busting up some favorite shibboleths:

1. “A passion for anonymity results in anonymity.” Dead wrong. An unbridled passion for anonymity leads to an aura of secrecy; to the press, forbidden fruit becomes far tastier than the same fruit lying on the table. Thus, the “passion” leads but to greater publicity, usually unfavorable. The only way to be relatively anonymous is to be relatively available to the press; after the first flurry of interest, if you handle it right, you can keep press interest on a back burner.

2. “Recognition that the President is surrounded by brilliant men detracts from the President’s own billiance.” Baloney. Nixon isn’t Johnson. The measure of a President’s stature is partly the men he trusts and surrounds himself with. That’s been Nixon philosophy from the start.

3. “A Presidential assistant should be too busy to afford to take time on his own public relations.” If he appears to be too busy, then he seems not to be on top of his job; this puts the President in a bad light as one who overloads people.

4. “But I really prefer to be unknown. I don’t like the public eye.” There are a lot of other things a Presidential assistant prefers — sleep, vacations, family time, security — and he gives those up, too.

Who is an assistant to make decisions on the basis of what he prefers? Nobody suggests that an assistant to the President become a spokesman or a front man. He should stay in the background as much as he can. But in this day and age, the best way to stay in the background is to give occasional backgrounders to influential writers.

Let’s assume you buy the idea that occasional exposure is the way to avoid sudden bursts of overexposure. There are three ways to approach the problem:

1. Defensive: (a) “I’m not really very important.” Nobody believes this; credibility problem. (b)”Any good executive could handle this job.” Then why you? Cronyism? President can’t find a really top executive? c) “My job really isn’t very interesting so there can’t be much to write about.” If this is so,then the government is not interesting, and dullness should not be our hallmark.

2. Offensive: “Hey, pay attention to me.” This does not work, and it is out of character for you anyway.

3. Missionary: The Assistant explains in a positive manner those areas of his work that reflect well on the President’s method of operation. He develops a set of public missions, and each interview he giives is a step in explaining one or more of those missions. In this way, he is not selling himself — he is helping sell an important facet of the Presidency.

Here we are down to the short strokes. What clear impression should H.R. Haldeman be leaving with interviewers? What messages can you uniquely deliver publicly that will benefit the Administration?

1. Fermentation of Ideas.

Wrong way to present this: Haldeman’s operation sees to it that nothing reaches the President that has not been fully “staffed out”. The President’s time should not be wasted with half-baked ideas, or thoughts that come in “out of channels. ”

This is bad presentation because it presents your operation as a barrier, “insulating” the President from work of genius or daring, watering down provocative plans until they become bland committee recommendations. It also suggests that the President is not discerning enough to recognize an idea as half-baked, or wishes people to stay confined to rigid departmental lines. Which is not so.

The right way to present this: This administration regards nothing more valuable than a good idea. To make certain that ideas are not £lung around and forgotten, we have set up a process to bring good minds to bear on good ideas, which stimulates further and deeper thinking.

When an idea comes into the President’s office–whether it’s a better way to spend money, save money, or have the President do something that costs nothing but makes a point — Haldeman’s staff starts the cross-

fertilizing.

When it reaches the President’s desk — fairly quickly — it contains the original idea as first presented, with back-up comments, objections, amendments and further thoughts by those who should have an interest. It is neither harmonized nor homogenized: the President is interested in seeing conflicting views so that he can make decisions with ideas and facts in context. And when the idea originates with the President, he has a right to see it refined and thought through by his staff.

Result: a fermentation of ideas within the administration, not all good but even an idea that is off base can stimulate another that will work.

One of the Haldeman staff functions is to keep the idea pot bubbling.

2. Using the Golden Bullets.

Each minute of the President’s time is a kind of golden bullet, too valuable to the nation to waste on scattershot meetings or premature decisions.

Wrong way to present this: Haldeman the doorkeeper, zealous protector of the President from seeing “unimportant” people, super-efficient organizer of the President’s schedule.

The President is not a robot to be “programmed” — he is a man who needs to make his time count.

Right way: Haldeman recognizes two responsibilities to every meeting. One is the responsibility of the visitor to the President; the other the responsibility of the President to the visitor.

Haldeman makes sure that when somebody needs to see the President, he is prepared to make his own appointment count. Excluding courtesy calls and private chats, each appointment should have a purpose: to explain; to request action, to brief, to persuade. The visitor is best served when he has a clear idea what he wants out of the meeting.

The President’s responsibility to the visitor or the council he chairs is to be prepared for the meeting: to be able to think about it in advance, to marshal the facts, to know’what questions he wants answered. ‘The Haldeman staff helps the President do this. Result: Snap judgments averted, sound decisions speeded up.

3. The Avoidance of Unnecessary Crisis.

There are enough crises that are an integral part of the Presidency without permitting predictable events to become crises.

Wrong way: The President’s schedule is meticulously prepared long in advance, rigidly adhered to, with no room for a sudden thought or whim or deliberate change of plan.

Right way: When an appearance or event is scheduled, an orderly process of preparation must go into action. A series of deadlines is set up, backdated from the appearance; staff has a chance to think about it, to plan their work, and to submit ideas and material enough in advance for the President to see if it is what he wants. The President is not then forced to the wall of deciding on inadequate material or no material at all.

This averts the all-night, frantic state of mind that all too often has occurred in the government — which causes mistakes, exhaustion, reacting rather than acting, being dominated by events rather than helping to shape them.

4. Follow Through.

The Haldeman’staff’s official flower is the Forget-Me-Not, which checks to see what is happening on ideas and decisions.

Wrong way: Nag, nag, nag. Right way: reprise of the ideas-are-valuable theme. We will not permit a plan or program to fall between stools. It can be killed, but by decision and not inaction or lethargy.

Upon leaving office, President Truman is reported to have said, “Poor like. He’s going to get behind that desk and push a button and expect something to happen, and it’s not going to happen.” Haldeman’s job is to see to it that the button is connected to something that reports back.

This system also protects against phony deadlines. Too often, deadlines

have been set that make it impossible to do a job well; the Haldeman

staff, by checking before the actual deadline date, can “re-negotiate” a

deadline to make certain the job is not just slapped together. This way,

the President knows how far along many things are before they come to him.

There may be a half-dozen other missions that you can think of; frankly, these are only those that appear to one man on the periphery.

But if you sell these, you will get across the message of good organization, intelligent planning, sensitive dealings with people, and a creative

process that permits the American people to have what amounts to a President and a half.

Which is why I urge you to drop the “machinery” metaphor, and the “input”, “program”, “print-out” computer jargon. The Presidency is not a machine requiring your lubrication; it is the human brain of our body politic, and you are at the center of its nervous system.